walsham forcep

Technique

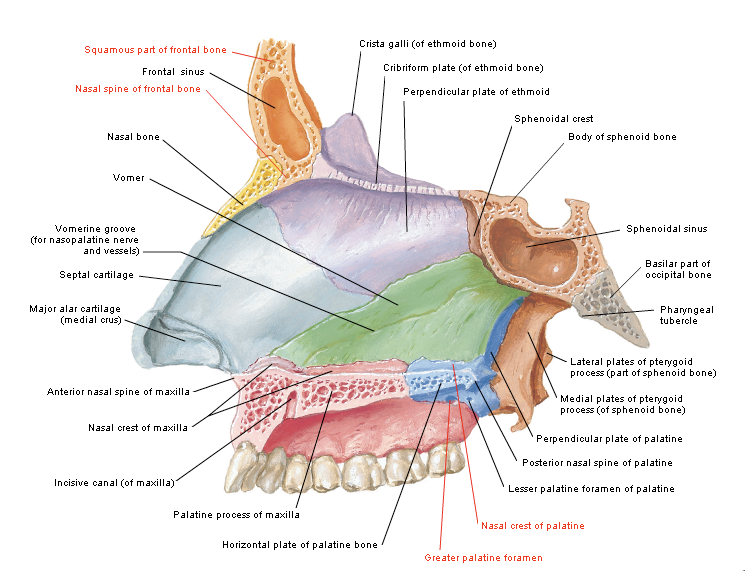

Nasal pyramid fractures should be reduced first, followed by nasal septum reduction.

Explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the patient. Obtain a signed informed consent, if possible.

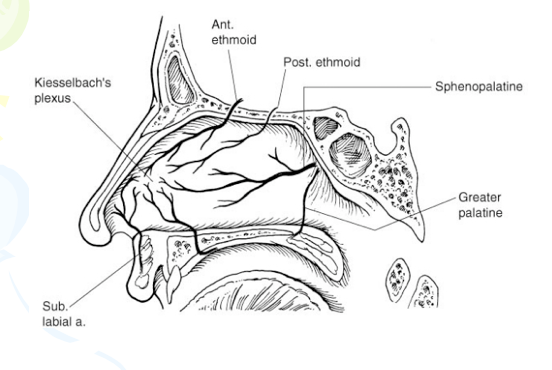

Deliver appropriate anesthesia. For details, see Anesthesia.

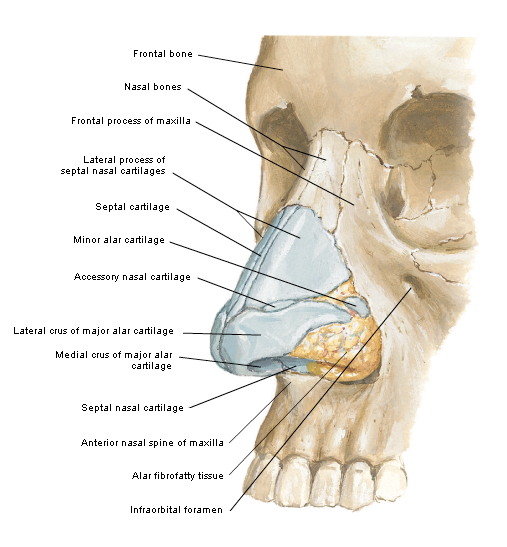

To reduce nasal pyramids, measure the distance from the alar rim to the depressed fragment externally. Mark position with thumb. Reduce depressed side of nose first.

Insert Boies or Salinger elevator into the nose under the depressed fragment. Apply steady outward pressure on the posterior aspect of the nasal bone. Control outward pressure with counterpressure exteriorly with the other thumb. Fragments may need to be molded into the proper position.

Nasal bone reduction.

If unable to reduce with elevators, use Walsham forceps to directly grasp the nasal bone. Insert one blade beneath the bone as the other blade is opposed on the outer skin surface. Manipulate the bone into position.

Check for septal reduction. If not adequately reduced, use Asch forceps to elevate the nasal pyramid while applying direct pressure to the displaced portion of the septum until it is moved back into the proper position.

Septal reduction with forceps.

Check for septal hematoma (drain if present).

Stabilize reduction with internal packing (eg, Vaseline gauze or 8-cm Merocel) and an external splint (eg, Thermaplast, Aquaplast). These external splints require intense heat for activation and molding, so the nasal dorsal skin should be protected with Steri-Strip bandage application prior to placement of the splint.

Remove packing in 5 days and remove nasal splint in 7 days. While the nasal packing is in place, the patient should be on an oral antibiotic with adequate Staphylococcus aureus coverage (eg, cephalexin) in order to prevent sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome.